Simple Pro Hacks for Shooting Beautiful Backlit Photos (VIDEO)

This 10-minute tutorial begins with a question for those of you see captivating backlit photos with beautiful golden tones and think to yourself, “why don’t my photos look like that?” There are a number of challenges with shooting under such conditions, and the tutorial below explains what they are and how to overcome them.

Instructor Simon d’Entremont is a notable Canadian photographer who specializes in nature and wildlife imagery and the occasional portrait. In this 10-minute episode he demonstrates the necessary camera settings and techniques so you don’t end up with shadowy silhouettes when backlight is the name of the game. He also explains how to include eye-catching sun stars for added impact.

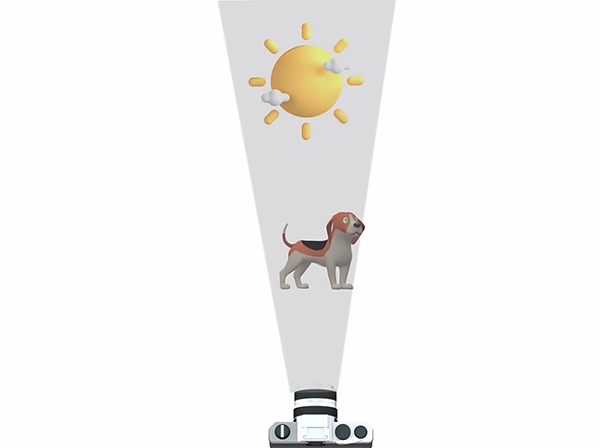

As the term implies, backlight occurs when the sun is behind a subject and can cause all kinds of problems with color fidelity, contrast, and exposure. Under these circumstances the part of your subject facing the camera is in shade, while surrounding areas are really bright. When this occurs the implications for achieving a correct exposure are obvious.

Simon discusses the fundamentals of backlit photography, one of which is that it’s best to shoot when the sun is low in the sky. At these times the light is less harsh “as it needs to go through more atmosphere to reach your camera’s sensor.” Simon notes further that “the atmosphere scatters shorter wave lengths like blue colors—leaving beautiful red and orange tones in their wake.

Thus, when the sun isn’t high in the sky the dynamic range of a scene is greatly reduced—making it easier to capture brighter tones without blowing out your highlights. Tip number two is best described by Simon: “the fluffier or furrier the subject, the more interesting rim light will surround them.” Simon illustrates how this works and contributes to photos with an artistic effect that can be quite “glamorous.”

In other words, portrait subjects with long flowing hair are perfect for backlit portraits, as are furry subjects for wildlife shots. As Simon suggests, think baby chicks and furry foxes. The magic of rim light occurs when the sun is able to partially penetrate the edges of a subject to create an appealing halo effect.

The foregoing is barely a taste of the techniques you’ll learn, and they’re all easy to understand and employ. By the time the video concludes you think of backlighting as a bonus, rather than a difficult obstacle that must be overcome.

Simon’s instructional YouTube channel is a great source of tips and tricks—especially for those who shoot and edit outdoor photographs, so take a close look and up your game.

We also recommend watching a tutorial we posted recently from another accomplished shooter, explaining a variety of simple pro techniques for capturing alluring outdoor portrait photographs.